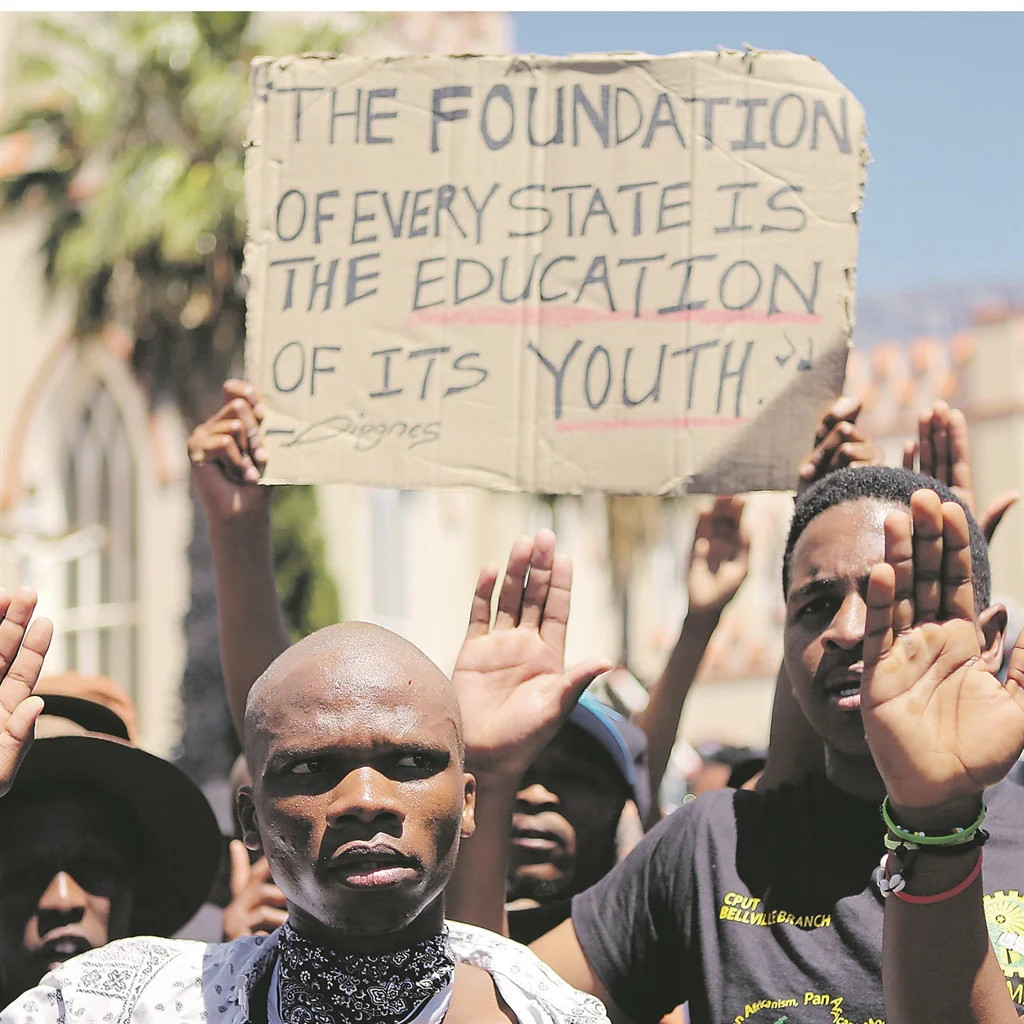

Our country is rife with challenges! Unemployment, poverty, crime, poor service delivery, sewage spillages, diseases, potholes, lack of proper medical services, gender-based violence, gangsterism, educational challenges … Is that what the field of the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSSA) has achieved thus far?

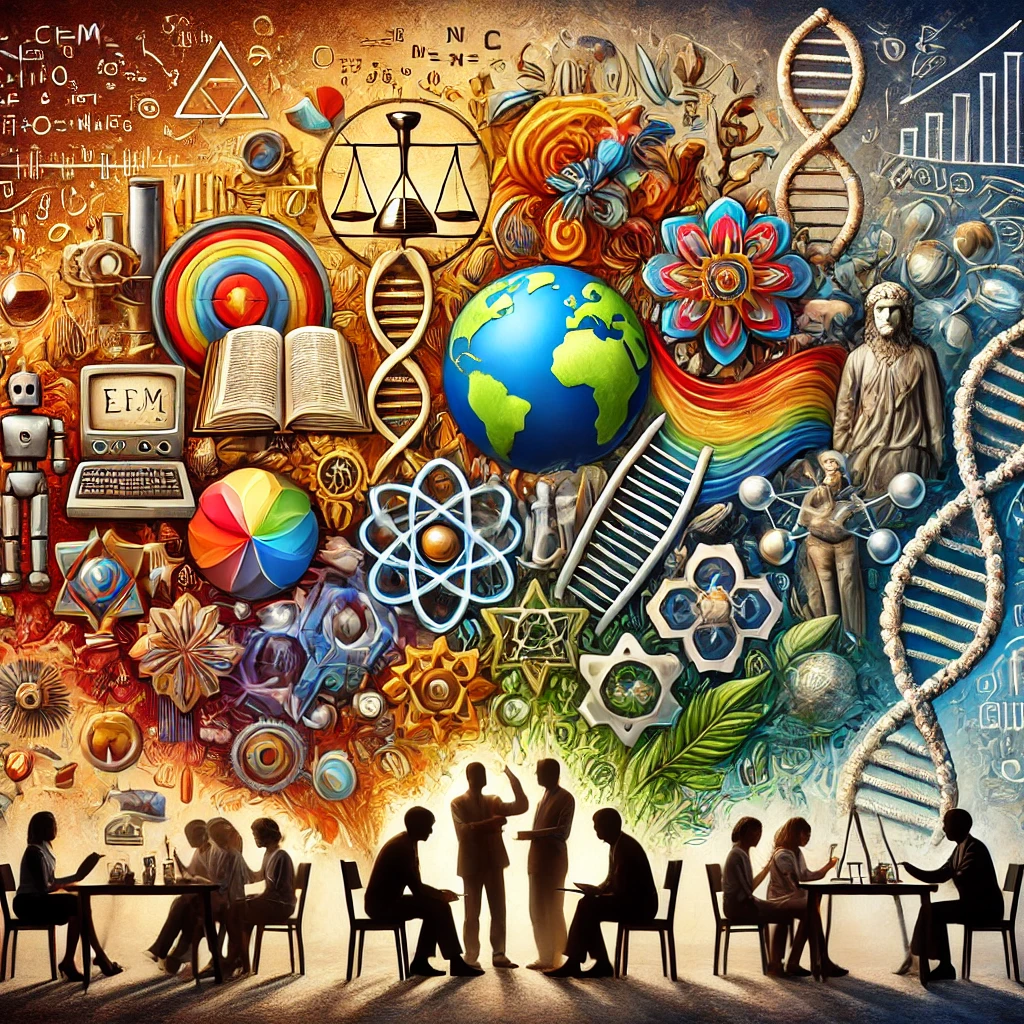

Humanities scholars and researchers work diligently to expand the field of the Humanities and Social Sciences, striving for excellence and quality while finding solutions to the global challenges society faces. Yet, recognition is given to Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), deeming them the main contributors to economic development, technological advancements, and, in education, to critical and analytical thinking. But what about Humanities, Social Sciences and even the Arts contribution?

Unfortunately, supranational inequalities still exist, especially within higher education. One would think that the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS) endeavour to realise and take the Charter for the Humanities and Social Sciences forward would have notably closed the gap in this regard. The NIHSS has, since its existence, strived to build on driving cooperation between institutions, establishing national and international communities of scholarship, advancing norm-driven internationalisation, scholarship, research and ethical practice in HSSA, and fulfilling their social responsibility and equity roles within society. Despite their bold initiatives to improve the higher education landscape, it remains a drop in the ocean in terms of the challenges we faced and are still facing today.

For me, it is obvious that the Charter has not been taken seriously. Personally, I don’t think it has achieved what it set out to achieve. I think people don’t even know about the Charter and what it has set out to do. This is no surprise, especially since there is no platform to review what has been done or achieved, leaving no space for making improvements or recommendations, let alone making people aware of the Charter’s existence. I believe that if the Charter’s proposed approach had been followed from the onset, then it would have succeeded in what the country should look like.

In essence, the Charter emphasises that HSSA is responsible for addressing the needs of society, building ethical, responsible citizens, and developing a strategy that will bring about positive change. Well, then, I think it’s time we go back to the drawing board and actively and aggressively undertake to do just that! Because all we are now left with is that the Humanities, including the Social Sciences and Arts, is still very much a neglected terrain. If the Charter had been taken seriously from the start, it would have reflected in universities’ curriculum and the plans they had for acknowledging the field of the Humanities, Social Sciences and the Arts. We would not be where we are today if we included the Charter and what it stands for when it was introduced the first time.

The Charter was established in an attempt to actually challenge higher education institutions to make significant efforts to tackle the lower-order status of the Humanities, acknowledging it as part of mainstream disciplines. The hierarchy discrepancy is seen in HSSA disciplines receiving lower institutional status compared to STEM disciplines, less funding, and fewer research opportunities. This hierarchy among disciplines creates chaos and confusion, leaving education in a real crisis!

Clearly, we have not done our homework properly. Universities are like factories churning out graduates; yet, there is no coordination, no mapping, no plan for these graduates. The country is not acknowledging all disciplines, so how can HSSA then become part of the knowledge economy? For me, it’s simple: Disregard knowledge imperialism, acknowledge the importance of transdisciplinary approaches, refute any form of discipline hierarchy, and collaborate among different stakeholders to bring about positive change … positive change in all spheres of life!

I mean, HSSA is key to making higher education, for example, more responsive to and inclusive of the global challenges humankind faces. Studying people within their social, cultural, psychological and political milieus contributes to our understanding of their behaviours and decisions. Also, this is how we get to understand the importance of our history, culture and philosophies, shaping future academic endeavours.

Furthermore, improving the quality of research positively and significantly impacts societal transformation, enabling scholars to inform policies and programmes aimed at improving people’s lives. Then why keep giving preference to STEM disciplines as if life is all about science? Perhaps it is the belief that science is about hard evidence, with the stigma around research in the Humanities that it is based on opinions. This is evident in publications, ranking of journals and citations involving the fields of the Humanities, Social Sciences and the Arts. If only we could realise and appreciate the valuable research and scholarly contributions of HSSA to humankind. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve been dictated by scientists as if nothing else mattered.

It is time we realise and acknowledge that not all answers are found within STEM disciplines because then, and only then, are we on the path to achieving greatness. We need to be open-minded about new and novel ideas and perspectives introduced by HSSA, continuously seek innovative breakthroughs, and not unnecessarily be too careful to challenge existing boundaries.

We need to deepen the debate and take the fields of the Humanities and Social Sciences more seriously in this country. This is not easy, especially with differing ways of seeking solutions to problems, ineffective communication, differing viewpoints, and different ways of knowing. However, this actually allows for dialogue among different entities, augmenting critical thinking, revolutionising knowledge, and crossing traditional boundaries, subsequently empowering and inspiring people from all walks of life.

It’s important to acknowledge that deepening the debate in Humanities is not limited to one specific challenge, though. There is a legion of challenges that need to be addressed, with none having preference over the other. We are still challenged by issues, such as poverty, inequality, poor service delivery, crime, violence, alcohol and drug abuse, gender discrimination, to name a few. These challenges are real, ultimately leading to the collapse of communities on a daily basis … and it is in these spaces that desperation comes into play! In this regard, it’s time to acknowledge the overall importance of Humanities. We need to showcase our commitment to finding solutions to critical and relevant current issues, seeking transformation and change, and ultimately aiming to uplift society. If left neglected, the way forward looks bleak.

Furthermore, the issues around language and linguistic imperialism, decolonising the educational curriculum, and an unwillingness among some to work transdisciplinary and transform programmes packaged with an apartheid approach are still a reality within higher education. Let’s face it: Higher education plays a critical role in taking the lead with how we are going to move forward in this country!

I think if we did not have the issue of linguistic imperialism, then half of the battle would already be won. With South Africa’s unique and diverse cultural landscape, it would be ideal if we could succeed in the endeavour of translanguaging in higher education institutions. This would ensure that academic content is taught using available linguistic repertoires to engage, collaborate, acquire and understand complex and difficult concepts, enabling students to develop sound academic language practices, acknowledge different ways of knowing, and positively contribute to their social and emotional development.

Also, we need to critically debate about repackaging the curriculum content. We continue teaching History, Philosophy and Political Science, for example, as a colonial mandate. This should change. It’s time to ensure redress in how we offer programmes within the Humanities. So, let’s endeavour to reshape the foundations of the education system, questioning what constitutes valid knowledge, including who decides what is valid knowledge. Believe Humanities should be part and parcel of knowledge transformation and the knowledge economy. This will inspire and shape future ways of thinking, creating a liberating, empowering and inclusive educational system.

Unfortunately, it seems that we haven’t done anything in this regard. Now I ask myself: Why are we not learning? What is holding us back? Are we merely paying lip service to renowned scholars, activists and trailblazers in the Humanities, or are we actually endeavouring to bring about change, transformation, and social justice? We need to seriously contemplate the future of the Humanities, Social Sciences and the Arts in South Africa!

I want to commend the University of the Free State for its initiative in this regard. They hosted a colloquium from 27-29 August in which the Charter was discussed in-depth, and the challenges of HSSA unpacked, explored, and critically debated, a much-needed and relevant event that will likely yield solutions to the current imbalances, inequalities and injustices experienced within this field … something we battle with in the South African Deans Association (SAHUDA) in fighting for racial imbalances and inequalities in higher education and actively searching for epistemic justice.

For me, I hope we will finally find ways to move forward and harness HSSA, evidently securing its rightful place alongside STEM disciplines. If we understand the combined value of HSSA and STEM, then we are in a position to holistically address complex problems, ultimately drive innovation, and revolutionise the higher education landscape.