The news of the passing of Reverend Jesse Jackson arrives with a weight that is both public and profoundly personal. To the world, he will be remembered as a towering figure of the global freedom struggle, a relentless advocate for civil rights and a moral voice that refused to be silenced. To South Africa, he remains a steadfast ally during the darkest years of apartheid, a leader who spoke our name in corridors of power when our own voices were forcibly muted.

But to me, he was something more intimate still: a mentor, a family friend, and a guiding presence at a moment when my life stood at a critical crossroads.

Exile is not merely the condition of being displaced from one’s homeland. It is also a slow erosion of certainty, an invisible unmooring of identity. One adapts to new cultures, new accents, new systems of meaning. One learns to succeed within them. Yet, in that process, something essential can begin to fade.

I came of age academically within the venerable walls of Stonyhurst College, a prestigious Jesuit institution in England that offered intellectual rigor, tradition, and a clear pathway to elite British universities. As I completed my O Levels and A Levels, the next step seemed self-evident: University of Oxford or University of Cambridge.

Yet my late father, Drake Koka, perceived something beneath the surface of this apparent success. He feared that in mastering European intellectual traditions, I was slowly drifting from the grounding of my Blackness and from the historical consciousness that had shaped our people’s resistance. I was a young South African in exile, excelling academically, yet increasingly distant from the spiritual and political inheritance that defined who I was.

It was out of this concern that my father reached out to the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

Jesse immediately understood what was at stake. He did not frame the issue as a rejection of excellence, nor as a detour from ambition. Instead, he spoke of grounding, of anchoring and re-centering a young man before sending him further into the world.

It was Jesse who proposed through Ida Wood of the Phelpstokes Foundation that I spend time at his alma mater, North Carolina A&T State University, where his sons, Jesse Jr and Jonathan, were studying. The intention was not to replace my academic aspirations, but to shape the person who would pursue them.

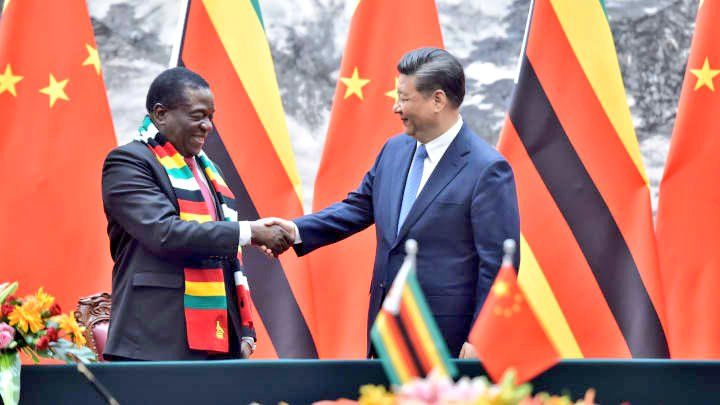

[Image: Robert R. McElroy]

That decision proved transformative.

North Carolina A&T was more than a university. It was a living testament to Black excellence rooted in self-definition rather than imitation. Here were students who spoke with confidence born not of inherited privilege, but of collective struggle and purpose. I encountered a tradition of scholarship that did not require the erasure of identity. A culture of excellence that celebrated Blackness rather than treating it as an obstacle to overcome.

At the centre of this world stood Jesse Jackson.

In public, he was known for his thunderous oratory and commanding presence. In private, he was defined by warmth, attentiveness, and an extraordinary generosity of spirit. The Jackson household functioned as a crossroads of the movement. Conversations flowed effortlessly between domestic concerns and global politics, between scripture and strategy, between laughter and solemn reflection. Jesse listened with the same seriousness to young people as he did to seasoned leaders. He challenged us to think, to articulate, to defend our ideas and, above all, to understand why we believed what we believed.

Through my friendship with his sons, Jesse Jr and Jonathan, I found not only companionship but fraternity. We navigated together the complexities of growing into ourselves under the long shadow of history. We explored life and curiosities as young men on campus. Met our prospective wives and accompanied each other to the alter. When I got married, Jonathan became my best man. Our debates, aspirations, and uncertainties unfolded within a home that treated political consciousness as a daily practice, rather than an abstract exercise.

Summers spent at Jesse Jr’s home in Chicago and time at his birth home in South Carolina became, for me, a parallel education. Thanksgiving gatherings were not merely family occasions; they were assemblies of elders, activists, artists, clergy and students whose lives had been shaped by the long arc of struggle. These were spaces where history was not frozen in textbooks but lived, debated and extended.

Jesse Jackson often spoke of what he called the “river of struggle”. The idea that none of us begins at the source and none of us controls the final destination. We inherit currents shaped by those before us, and we bear responsibility for shaping those that follow.

In one quiet conversation about South Africa, exile and the peculiar loneliness of fighting for a country one cannot physically touch, Jesse said to me: “Never let anyone make you choose between being African and being global. You are both. You must be both.” That sentence has remained with me ever since.

Through Jesse, I came to understand that the politics of Black Consciousness in South Africa and the traditions of Black Liberation in the United States are not separate conversations, but different dialects of the same language. The insistence on psychological liberation articulated by Steve Biko found resonance in Malcolm X’s call for mental decolonisation. The vision of shared humanity embedded in the Freedom Charter echoed in Martin Luther King Jr.’s conception of the beloved community. Jesse did not present these traditions as competing ideologies. He presented them as a continuum.

It is also important to note that I was not the only South African finding political and personal grounding within Jesse’s orbit during those years. Alongside me was Kgosi Mathews, who later served as Jesse’s Special Assistant for a number of years. Kgosi came from a proud African National Congress lineage. His grandfather, Z. K. Mathews, was a renowned academic and one of the intellectual architects of the liberation struggle, deeply rooted in the traditions of the African National Congress. I, by contrast, was a child of the Black Consciousness tradition. Yet within the Jesse Jackson camp, these histories did not collide, they converged.

Our debates were rigorous, but never hostile. We challenged one another, sharpened each other, and discovered how our respective traditions were less rivals than complementary currents of the same river. Under Jesse’s guidance, we learned that political maturity required both conviction and generosity: the ability to hold one’s lineage with pride while remaining open to synthesis. We learned that style, presentation, and comportment were not superficial, but part of political communication. From how we dressed, to how we spoke to how we carried ourselves in public spaces. Jesse taught us that leadership is read long before it is heard.

When he invited me onto his Presidential campaign trail, I witnessed firsthand the toll and the nobility of public service. I saw exhaustion, sacrifice and disappointment. But I also saw an unshakeable faith in ordinary people. Whether speaking in churches, union halls or community centres, Jesse refused to dilute his moral message. He believed leadership meant calling people to their highest selves, even when doing so was politically costly.

Perhaps the most enduring lesson he imparted was simple yet demanding. Whatever you become, become it in service.

Not in service to recognition. Not in service to comfort. But in service to humanity.

Looking back, I now understand that my father’s intervention was an act of love rooted in foresight. He did not fear education. He feared amnesia. He feared I would forget who I was, where I came from and what obligations accompany privilege. Jesse ensured that I did not forget.

On behalf of my late father, Drake Kgalushi Koka, and my mother Maletlhare, I wish to extend our deepest condolences to Mrs Jacqueline Jackson; to the Jackson children Santita, Jesse Jr, Jonathan, Jacqui, Yusef, Jacqui Lavinia and Ashley. And to the entire extended Jackson family. Please know that you remain in our prayers and in our thoughts during this time of profound loss.

The world has lost a giant.

I have lost a teacher. I have lost a guardian of my becoming.

Yet I take comfort in knowing that Jesse Jackson’s legacy does not reside solely in monuments or archives, but in the countless lives he shaped quietly, patiently and with love. His voice may now be silent, but his lessons speak in how we walk, how we think and how we serve.

May his soul rest in Power. May his river continue to flow.

![A grieving widow [Image: WIF]](https://gsmn.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/black-woman-crying-.jpg)

One Response

Inspiring piece. A life well lived 😌.