For three days and two nights, tucked away in the quiet embrace of a farm, I sat with men who have lived more than half a century of South Africa’s unspoken histories. It was less a gathering than a council. Visible in our laughter, debate, and storytelling, yet guided always by an invisible hand of memory, sacrifice, and struggle.

I call it the Council, though it was never named as such. Sipho Mabuse and Khaya Mahlangu, two seasoned Saxophone Men, lifelong friends whose horns have carried both joy and protest through the decades. Between them lies more than fifty years of friendship and survival, their political lenses different but complementary: Sipho, anchored in national politics, Khaya leaning Pan-Africanist. Their instruments were never just for music; they were tools of reflection, weapons of resistance, and vessels of beauty in a wounded land.

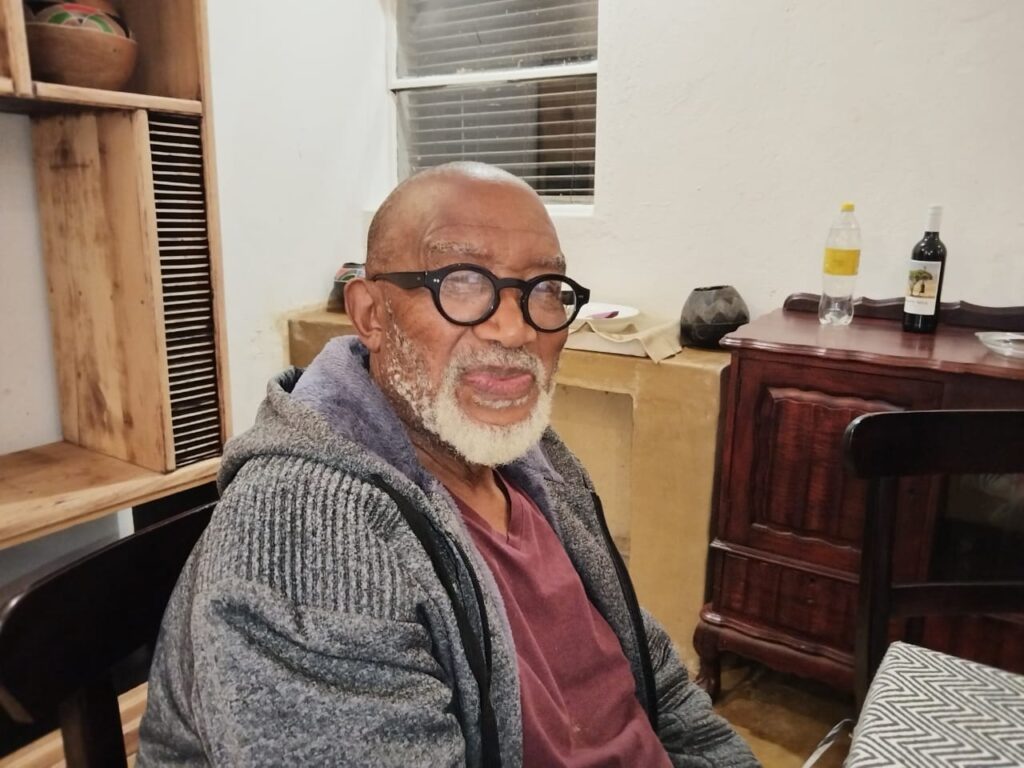

Beside them sat two hardcore exiles. Lentswe Mokgatle, whose underground work as an ANC operative could leave even the most sceptical listener in disbelief. His cover as a musician was so understated that many never suspected the weight of missions he carried. He had mentored me, the scholar who wandered into economics and jazz history, but who was always shaped by the teachings of Lentswe and others like him. For me, exile had meant books, lectures, and speeches; for Lentswe, it had meant clandestine movement, shadows, and codes.

Our circle widened with the presence of Sandile Memela, writer and thinker, a provocateur, his words as sharp as his questions. Then there was Russel Baloyi, the youngest among us, a rising figure in the political arena. What he lacked in years he compensated for with piercing curiosity, drawing us into explanations that forced us to reconsider even our most seasoned positions. In many ways, he was the reminder that councils must not be museums. They must pass on their fire.

The days on Lentswe’s farm unfolded in rhythm. Mornings carried the scent of strong coffee and long, slow conversations that stretched until midday. Afternoons blurred into politics, culture, cuisine as we took turns cooking exotic dishes, trading recipes and techniques as readily as we traded memories of exiles, betrayals, and reconciliations. Evenings, inevitably, slid toward confessions: of love and loss, and the children we had lost along the way. Each story carried its own silence, and each silence its own healing.

Music was never far. We curated it like archivists. When Sipho and Khaya spoke, you could almost hear the horns between their words, a counterpoint of history and improvisation. Lentswe’s stories of clandestine crossings were punctuated by quiet chuckles, as if secrecy had long ago given way to freedom. Sandile reminded us that words themselves are a form of jazz, improvised but structured, fleeting but permanent.

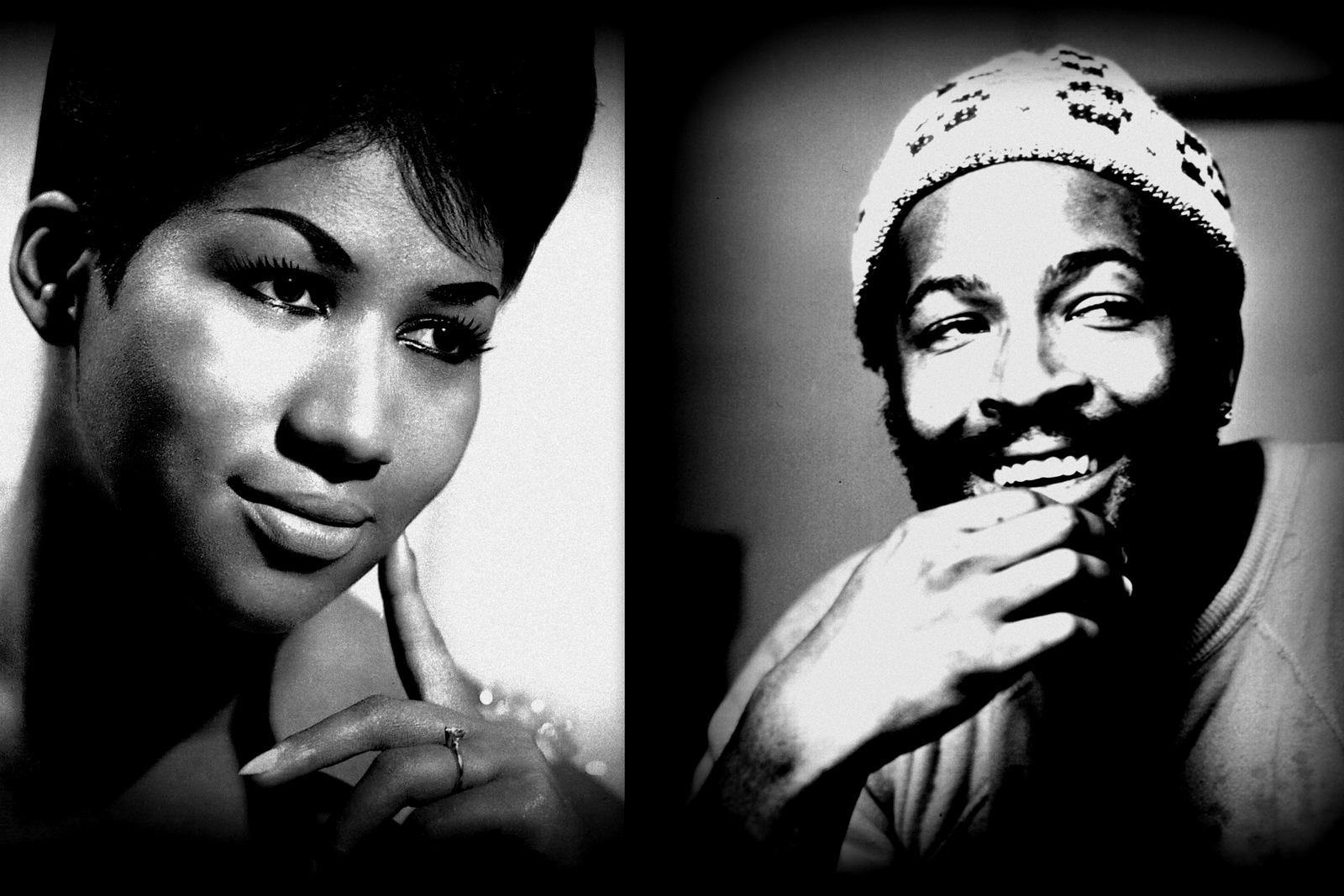

Soul classics from Marvin Gaye and Aretha Franklin weaving into Beethoven and Coltrane, before giving way to our own South African sounds. It was a potpourri of inspirations, each genre sparking new thoughts, drawing bridges between struggle and celebration.

Each of us had our Godfathers of sound, the ones who shaped our ear and sharpened our worldviews. For Sipho, it was the rhythm and resistance of Hugh Masekela. For Khaya, the big, searching horn of Coltrane. For Lentswe, it was the voices smuggled on vinyl through secret crossings. Miriam Makeba, Abdullah Ibrahim, and the chants of freedom songs coded as lullabies. And for me, it was Miles Davis. Miles was not just music; he was an attitude, a way of seeing the world through shifts, silences, and sharp notes. He taught me that dissonance could be as powerful as harmony, and that sometimes, to lead, you had to turn your back to the audience and force them to listen differently. My world was and remains shaped through his lens.

Naturally, this led us into endless backstage and travel anecdotes. Stories of musicians lost in airports, of instruments confiscated by suspicious border officials, of nights when the music outlasted curfews and threatened arrests. Sipho remembered once improvising with a broken reed and still pulling the crowd to their feet. Khaya laughed about sharing a stage with legends who forgot entire setlists but improvised into brilliance. Lentswe spoke of moving “messages” hidden inside record sleeves across borders, disguised as gifts, but carrying instructions that could change the course of a campaign. These tales kept us in stitches, laughter rolling like the bassline of a groove, reminding us that even in the darkest days, joy was never absent.

And the young man, Russel, absorbed it all. He asked about exile, about what it meant to sacrifice one’s family for a cause, about the cost of being too loyal or not loyal enough. He questioned the use of jazz as metaphor for politics, wondering whether improvisation could be a principle of governance. He challenged our romanticizing of the past, even as he revered the resilience that carried us here. His questions reminded me of myself at a younger age; except he had the privilege of sitting inside the Council rather than listening from the margins.

One morning, we drove not far from the farm to lay to rest Molefe Pheto. Our comrade, writer, and exile brother. Standing on his soil, among former exiles and today’s political and cultural practitioners, it became almost a full circle. We buried not only Molefe but also fragments of our own exilic selves. There was grief, yes, but also a rare serenity. The sense that what had begun in the shadows of exile was now finding its conclusion in the open light of democracy, however flawed. The Visible Council carried Molefe with us back to the farm, our conversations sharpened by the reminder that time is finite, but legacy is not.

It struck me often that this council was both fragile and indestructible. Fragile because time has already claimed some of our comrades, indestructible because the Invisible Council, the ancestors, the martyrs, the giants whose footsteps we trace still guides us. Every argument we had about governance, every laugh we shared about youthful foolishness, every pause we made when grief pressed too close, was threaded by their presence.

By the third day, the farm had changed. Or maybe it was us who had shifted. The Visible Council was stronger, though not by agreement for we disagreed often, and sharply. It was stronger because of the visible act of gathering, of remembering, of tasting the weight of our lives together. Stronger because the Invisible Council, fathers, comrades, leaders, spirits had sat with us all along.

When I left, I carried more than memories. I carried clarity. Every time I leave Lentswe’s farm, I come out wiser not in the academic sense, though my training as a scholar is never absent, but in the fuller sense of wisdom: to cook with patience, to listen with humility, to speak with courage, and to love with awareness that loss is inevitable.

The Visible Council was not about us alone. It was about continuity. It was about ensuring that as we sit under wide skies, stirring pots, trading philosophies, and swapping stories of Godfathers and forgotten gigs, the invisible hand of history does not slip from our grasp.

And so, the Council endures.