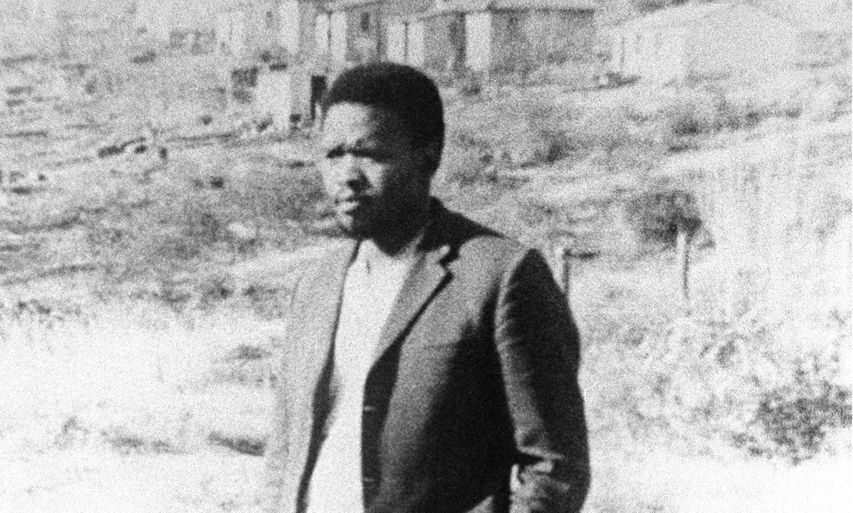

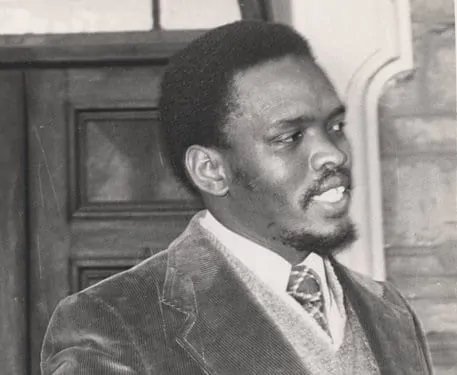

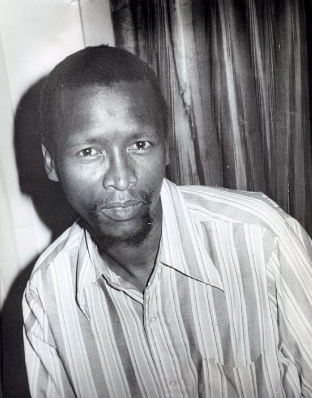

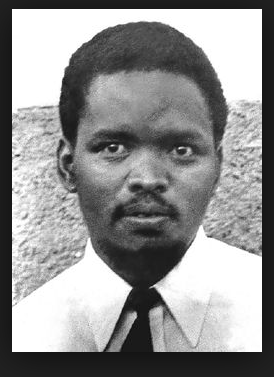

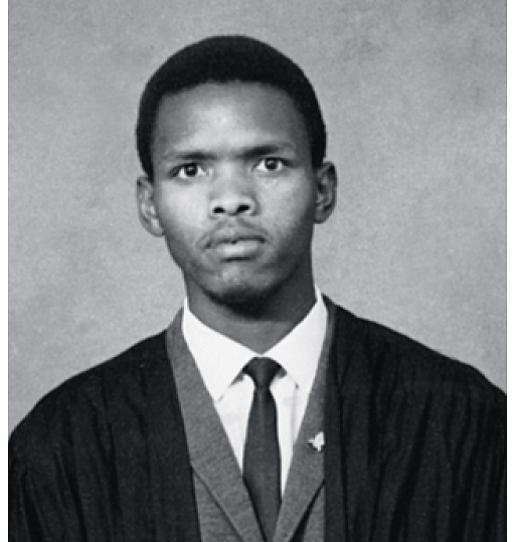

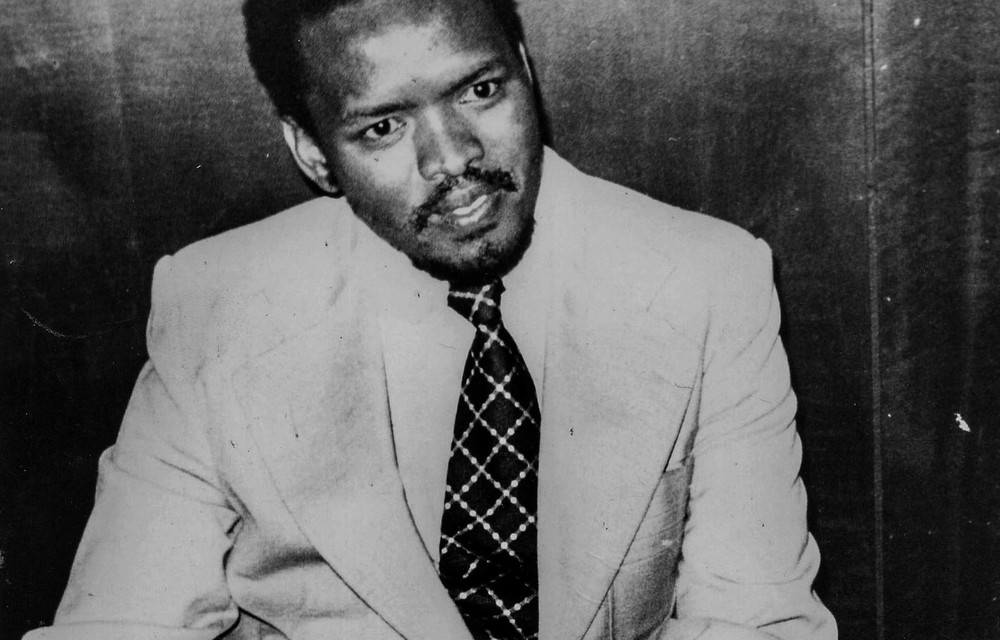

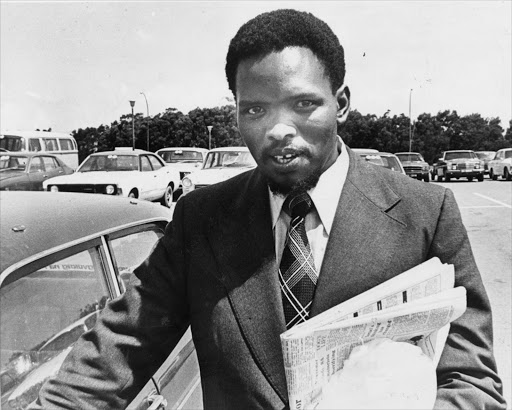

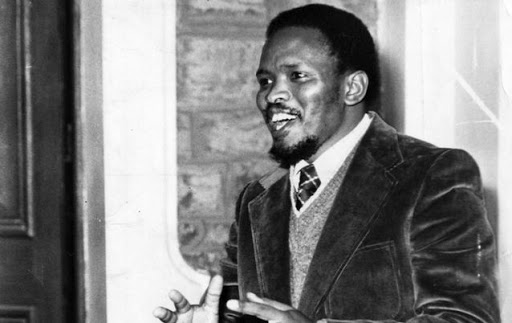

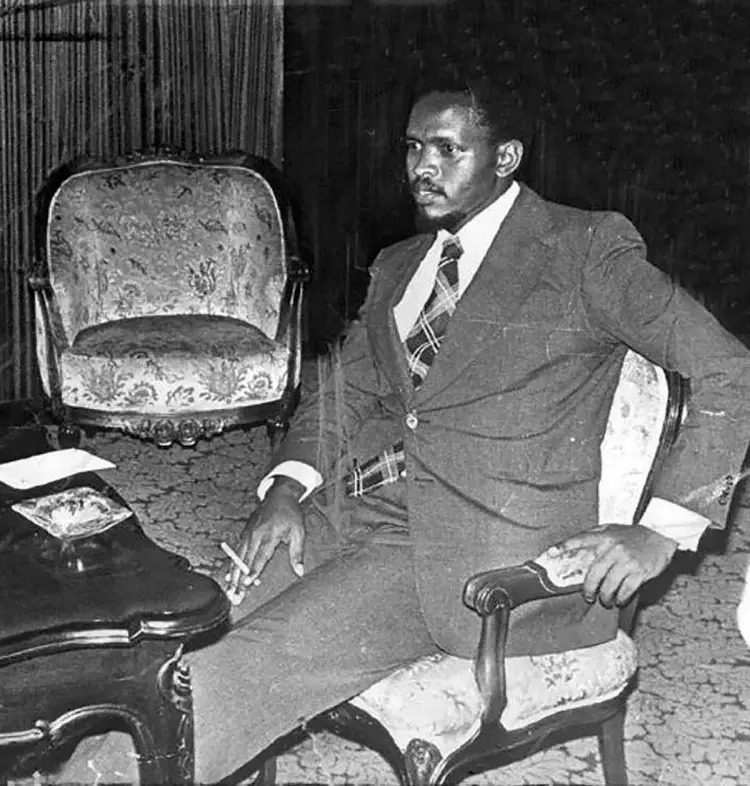

Nothing describes and summarises Steve Biko’s brief but sufficient life on earth as does the title of the legendary Alice Walker’s 2007 book, We are the Ones We have Been Waiting For: Inner Light in a Time of Darkness. While he died at the tender age of 30, he would have turned 79 this coming December. His seriousness to life and mature face in his photos belied the fact that Biko was a young person whose epoch-making political life was packed and confined within an eventful decade from 1967 to 1977.

Biko’s purpose of life was to bear the revolutionary torch and throw light from his inner energy in a time of darkness. It was a time of darkness that was characterised by the banning of the ANC and the PAC in 1960, and followed by the mass arrest of the political leaders and the imposition of the death sentence on a number of them. The rest were imprisoned on Robben Island either for life or long sentences. Those who escaped imprisonment were either killed in their magnitudes, or skipped the country for exile. The political Biko germinates in this period that generally referred as a “political lull” characterised by fear, disorganisation and leaderlessness in Azania.

His life was a divine script from the spiritual world. It was as though he knew that he didn’t have much time to live on this treacherous earth. Of 4 siblings, he was the third child of Mzingaye (home because of him) and Nokuzola (serenity). Mzingaye died on 31 March 1950 at the age of 34 when Biko was only 3 years old. Interestingly, Biko was given the names Bantu (People) and Stephen, which is the Anglicised version of the Greek Stéphanos which means honor, crown or wreath. Ironically, the words honor, crown and wreath precisely describe Biko’s life trajectory on earth. The Biblical story is known of a Saint Stephen who was regarded as the first Christian martyr who was stoned to death for his beliefs.

Could it be that Biko’s parents knew that their son would walk the spiritual path of Honor, Crown and Wreath? If they didn’t know, Biko seems to have known. Strangely, Biko was not so much interested in politics as a teenager. He was just enjoying his youthful life and indifferent to the fact that the dusty Ginsberg township was the PAC’s stronghold, while his brother Khaya was its activist. His childhood nicknames “Xwakuxwaku” (unprocessed appearance) and “Goofy” do illustrate the fact that he was a carefree soul. However, his remarkable intelligence got the Ginsberg community to be involved in raising funds for him to join his brother Khaya at Lovedale College in 1964. That’s where he got into trouble because of his brother’s association with the banned PAC. They were both detained by the police resulting in Biko’s expulsion, while his brother was charged and convicted but later released on appeal.

In this regard, Biko was recruited into active politics by the circumstances which we have come to know as the Black Condition. Biko later expressed agreement with this sentiment: “I began to develop an attitude which was much more directed at authority than at anything else. I hated authority like hell.” “Authority” here is a reference to the apartheid regime’s authority or white power structure.

In 1966 he enrolled at the University of Natal, Black Section, for a medical degree in and joined the white liberal students’ organisation, NUSAS. It didn’t matter that he was now at university and in the company of the privileged white students, the Black Condition revisited him in 1967 when the apartheid segregation laws made it a point that white and black students would not sleep at the same residences in Makhanda (then Grahamstown) at the Rhodes University. A church in the township had been arranged for black students to use as an uncomfortable accommodation that reminded them that they were black. That was when black students realised that they did not belong to, but accommodated in NUSAS.

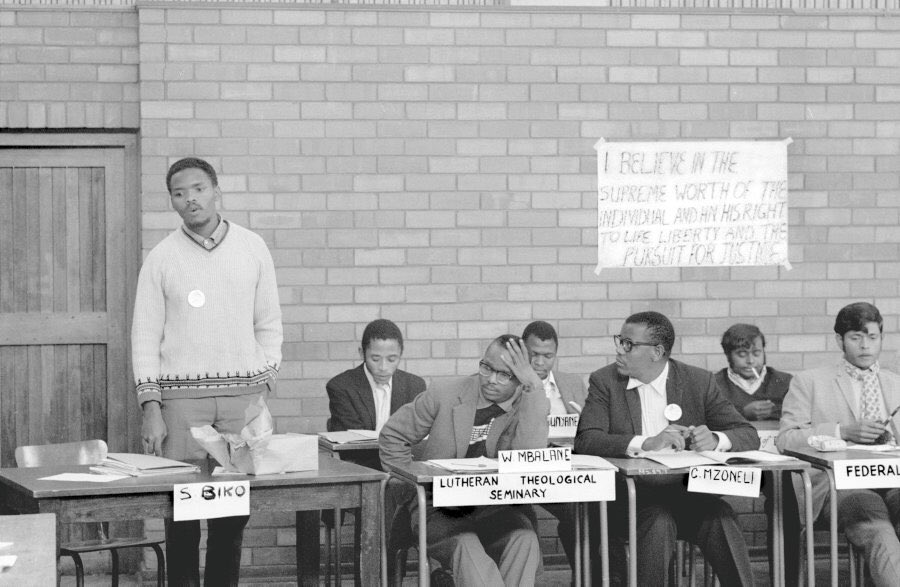

This was about the time when Biko realised that “We are the Ones We have Been Waiting for”. But his revolutionary practice predates this progressive phrase as was expressed in their straightforward and combative strategic direction that “Black Man You Are On Your Own”. Black students were no longer going to wait for white tutelage. They had sufficient “inner light” to empower themselves. They were their own liberators – the liberators they have been waiting for all along. It was in the womb of the University Christian Movement (UCM) in a 1968 Conference in Cumakala (Stutterheim) that the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) – SASO, to be exact – was conceived. It is an irony of history that the ideation of the Black Consciousness philosophy found fermentation within the context of institutional sources like the white liberal NUSAS and the Christian UCM. It probably explains why BC activists initially addressed one another as Brothers and Sisters, while some early revolutionary songs tended to be an implant of struggle lyrics on Christian hymns.

Biko was sure to be not the embodiment of the critical statement attributed to Benjamin Franklin that “some people die at 25 but are not buried until they are 75”. In terms of serving and living for the people, he was not going to be politically dead-alive. Accordingly, He wrote some of his seminal works from 1969 to 1972 between the ages of 22 and 25. Of course, he continued to contribute some internal policy writings as he did with the 1975 Mafikeng Manifesto under the caption Towards a Free Azania: Projection of a Future State that was first presented at the Black people’s Convention’s (BPC’s) Conference in Qonce (then King Williamstown) to afford the banned Biko some covert participation.

It is important for young people who helplessly drown in the defeatism that they are too young to shape and contribute in the discourse and praxis to liberate their societies and themselves, to take counsel and example from the young Biko. If we count Biko’s political age from 1967, we have to acknowledge that his direct and overt political involvement was punctuated by a 26 February 1973 banning order which meant he could not write or travel out of the Qonce district. That means Biko had only 5 years of free political activity within which he did everything that needed to be done to conceptualise, theorise and practice BC. The little but significant political and cultural work he could do during his banning was to be involved in self-help community projects under the auspices of the Black Community Projects (BCP). It was in that initiative that the Zanempilo Community Health Clinic was established in Ezinyoka village not far from Qonce. There were two more community health clinics like Solempilo in the southern Kwazulu-Natal (then Natal) and Isutheng in Limpopo (then Northern Transvaal).

As a community development model, the self-help projects were more than a simple and ad hoc welfare intervention. Rather, they were designed as an instrument to help refocus the people away from desperate dependency on the enemy for their livelihood. The self-help projects played a pivotal role in entrenching the basic tenets of Black Consciousness like self-reliance, self-initiative, self-definition, self-assertiveness and self-determination. By the reintroduction of the indigenous development model as a weapon of the liberation struggle, Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement were intellectually and practically denouncing the capitalist and enslaving principle of food security in favour of the revolutionary food sovereignty. In this revolutionary model, the access to food was based not on purchasing power, but on the commitment to work. These projects were not limited to the sphere of agriculture. They ranged from health institutions to heal the people; factories to produce goods like furniture: leather goods in Ezinyoka and Njwaxa villages; bricklaying in Dimbaza; agricultural scheme at the Mbashe River; Trust funds like the Zimele Trust Fund and Ginsberg Educational Trust; newspapers and journals like Black Review. These initiatives were aimed at the attainment of psychological and material liberation through cultural revival and conscientisation.

Let us remember that these self-help projects gained serious traction between 1972 and 1977. Of cardinal importance for the black youth is to take note that Biko did all this revolutionary development work within 5 years, and between the ages of 26 and 30. He was not going to wait until he obtained an academic degree, or until he was gainfully employed before he injected hope in the empty shell of the black person. He knew he could not do the work of liberation by abusing drugs and alcohol. He was quite aware of the weaponisation of drugs and alcohol by the system to destabilise the black family and defocus the black youth. Abuse of drugs and alcohol were sure to dim or switch off his bright light in a time of darkness among his people. He would not be able to discover and unleash himself as the one he was waiting for.

I venture to make the reckless point that Biko’s genius was really accentuated not when he wrote his seminal essays between 1969 and 1972, but when he appeared at the 1975 BCM Trial as a defence witness in favour of the 9 SASO and BPC activists. Biko had been banned for 3 years when this trial reprieve was available for him to march out of Qonce and voice his political views in a legal trial. It was an extremely dangerous balance between ensuring that BC was not stripped of its revolutionary substance, while also presenting it in a manner that would not jeopardise the case of the accused political activists. When he was writing his essays which were collated into the book I Write What I Like, Biko was in the comfort of his solitude where he could write and erase, arrange and rearrange, pause and restart at his own time and speed. It was not the case during the trial at the apartheid Pretoria Supreme Court. Though he had enrolled at Unisa in 1973 to study law through correspondence, Biko was not a lawyer. However, in his book The Eyes That Lit Our Lives, Andile M-Afrika records the observation of a BC activist and practicing lawyer Kgalake Don Nkadimeng who attended the trial:

“Steve spoke his mind in that court. He could display his intellectual superiority so superbly, and there were times when we – as the audience – would wonder whether Steve himself was the judge and the judge the accused. Judge Boshoff was surprised at the quality of the man and the testimony. It was clear that he never expected that he was questioning a witness who had written extensively on the philosophy which was on trial. He was so shocked that he almost stopped the trial.”

We will do well to remember that Biko was only 28 years when he was mesmerising and toying with apartheid judges and advocates. Biko was a candle that new it would not lose its light by lighting the other candles. By the time they blew its light on 12 September 1977, the whole of Azania was lit as evidenced by the fires of the June 16 Uprisings.

Let there be Light.